11/17 /2023

The Truckee River runs right through the middle of Reno, Nevada. Most visitors never see the river— they arrive through the airport or Interstate 80 to gamble or ski, transfer from their vehicle to a hotel, a casino, and back to a vehicle. But for some visitors who walk beyond the hotel-casino complex, and for many natives getting fresh air and exercise, the Truckee River is the heart of the city, where they come to refresh, escape or at least slow down. Nearby Todd Gilens has installed his long pavement poem titled “Confluences: Stream Science, Handwriting, and Urban Curbs.”

In recent decades Reno has constructed a “Riverwalk District” of waterfront plazas, parks, playgrounds, an outdoor theater, and bars and cafes to attract tourists and young partiers looking for a splash of outdoors with their food and drink. Similar to many other urban spaces, these plazas and benches have also been claimed by “street people.” The district features public art, most noticeably metal sculptures possibly inspired by the nearby Burning Man festivals which feature large 3-D constructions. They soar into the air, commandeering visual space, but don’t say much.

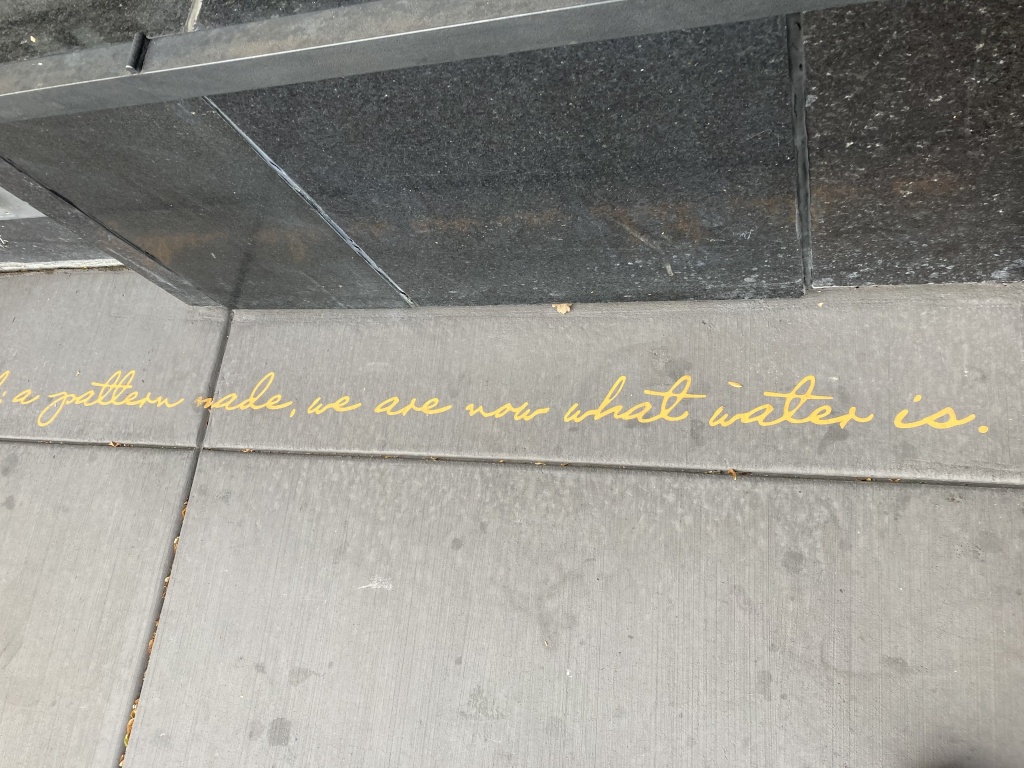

Todd Gilens’ watershed poem works in the opposite way. Its words do not reach for the sky, but cling to the ground on sidewalks or curbsides near the Truckee River. Only its color loudly vies for your visual attention with its highway-dividing-line-yellow. Everything else about the poem’s look is as subdued as the wind rustling the trees. Though it can be called a river poem, in appearance it is a ribbon poem, snaking its way from wherever the viewer begins, reaching into the distance. If you read enough, the poem’s descriptive range is ambitious, covering both the flood’s destructive flow and the aquifer’s saturated-earth creep, moving at a geological snail’s pace. It is not so much about humans, as about the saturated ground of our existence. So in its intent, “Confluences” is not modest at all. As the human race struggles to come to grips with the momentous abstractions and overwhelming particulars of climate change, learning about water as a part of this earth-body we inhabit has tremendous importance. But who will read grand themes of the poem when its visual form is so easy to overlook? Will it be embraced by enthusiasts who will read deeply while walking and stopping intermittently for hundreds of feet in Reno? Will it turn out to be a Quixotic gesture, a grand vision that will languish unseen in plain sight?

Before going further, I should introduce the poem in verse form, as I first read it on the screen. It is about 6,000 words, set in the natural world with humans only appearing indirectly. It is calm, accepting the world in flux, most impressed by how earth regulates itself, rather than bemoaning the loss of a canyon, a road, house, a mountain, or an individual plant, animal, or human life. Naturally the speaker of the poem is an omniscient voice:

Flows tug at edges, topples trees,

roots and trunks shift forces,

piling up debris, sediments and watercourses –

physicality is met and shaped,

boundaries of life and non-life

clasped in endlessness.

(Idyl, November 2022 draft)

Engineering projects and built environments are momentary alterations, eventually swept away by earth’s geological, hydrological, and meteorological forces. The speaker in the poem is not continually omniscient; periodically “we” emerges, sometimes to refer to the human view, but sometimes including animal cousins, and other beings of the natural world:

A walk in flow, a shimmering script

of bodies in motion over rough

or smooth; passages curling back

from ragged edges, we rise and spill,

pulse of treading rock and earth,

of life passing in pathways,

following change into our futures.

(Idyl, November 2022)

The poem has a clear overarching message: that water does not really come from the faucet, but from a complex natural process with biological, chemical, atmospheric, hydrological, and geological dimensions, through which the poet embraces infinitude and mutability. What appears in a moment as just sunlight, a tree, or stream, or mountain is always transforming into another form, and water’s flow manifests this transformation. Language is a minor theme, evoked as myth, story, metaphor, and most fundamentally as the cursive script of the poem itself that visibly trickles along the pavement. Periodically the poem returns to reflect on the notions that nature is like artful writing, that language, like water, has both systemic patterns and random collisions.

The digital version of the poem is in about twenty sections, (titles related to Reno streets and the number of characters on a section of pavement, necessary when affixing words to a sidewalk), but a walker-reader does not perceive those sections. If the whole poem were published in a book it might number 50 pages. End rhymes are rare, but other kinds of rhyme, half-rhyme and alliteration are periodic in a way that I find pleasant, familiar, not obtrusive. Included are pleasing scenes, here of that least visible of natural formations, the underground aquifer:

Drawn along the fissures,

surface suddenly in springs,

small miracles of relief

on forest slopes, the cool,

constant temperature of ground

emerging into bright, dry day.

But moist air and rising mists at dawn

show where water is,

and moves, below ground.

Active, sheltered, vital, slow,

a liquid glacier, aquifer.

Moisture read by plants and insects,

who see much more

precisely than we do: humidity,

a sip in cracks and drops enough

for beetle, bacteria, bee.

(FST 1, 2022 document)

Yet this is not traditional nature poetry. The poet spent years following University of California stream scientists in their Sierra Nevada field stations, as they measured changes in those watersheds through seasons of flood and drought. The poem brings us along with them:

what’s needed are sciences,

vocabularies, measurements,

attention and position,

some time and dedication,

circumstance to call and listen,

recognize, speak, and feel.

(Idyl 4325, 2022 draft)

But scientists are not approached as high priests of the holy mystery. Their methods are human and fallible and those methods must inquired into as well:

Our tools progress, it seems:

we measure great with tiny,

fast with sluggish,

distance and proximity,

with more precision than before,

power made from careful observation –

fine nets of data, automated sorting,

and perfection; seeing so far that things

disappear, and we come out

the other side, with other things

to discover there.

Our instruments accelerate

the speed of knowing, scope of

place, companionship,

but how to keep coherence,

when what we know is changing?

(Rvr 2, 5878, 11/2022 draft)

The poet’s work of bridging scientific with poetic discourses obligates him to work continually with metaphors for science, as well as evoking Greek and Latin myths such as Narcissus, Echo, and Achelous, but not however the myths or watershed practices of the indigenous peoples of the region.

“Confluences” runs along curbs and sidewalks in flowing script based on the handwriting of Claude Dukes, a Federal Water Master for the Truckee River for over two decades. Gilens found his handwriting graceful and beautiful, using it as the model for an original font to typeset the poem. Dukes was a native son of Nevada, and wrote water policy for the state, but he is not a character in the poem.

Some readers may wonder if setting a text in cursive excludes readers, given that instruction in cursive script writing has been declining for decades. Others, realizing that written poetry is already considered a nerdy effete discourse, would dismiss the importance of cursive as a medium for poetry. I myself have forgotten some of my cursive instruction, and can form a capital F or Q with great difficulty, but I had no problem reading the Claude Dukes font, and found it pleasing. It is debatable whether the font will be legible to many readers. But the cursive font is not the most serious obstacle in reading “Confluences” on concrete pavement. More troubling are the issues that I would label physical-mental, environmental, and textual.

First is the the physical-mental issue. Normal mortals can only read English from left to right, but when I read “Confluences,” I could not always walk to the right. I had to spend as much time going to the left as right, and for that left-going time, I could not read what I saw. Also the size of the cursive font, roughly 4 to 5 inches high, can be read from a standing position, but after a few minutes such reading could only be done with a certain strain (I admit I am 68, and my distance eyesight is weakening— but I had read the poem before, which should have put me at an advantage for easy reading). On the other hand, the script’s brilliant yellow, adopted from traffic markers, is definitely an asset to outdoor reading, as is the highly legible cursive font. Still the size and the thinness of the cursive font make the words appear wispy and ephemeral rather than bold. And I am embarrassed to admit that walking-reading was harder than I thought it would be. Despite the fact that the poet originally composed the verse in short lines, and designed gaps in phrases on the pavement where the poem’s topic shifts, my walking-reading pace never became comfortable and natural in my two days of practice. I controlled the pace, but was always shifting my walking speed. I moved right to see the next phrase, paying attention to bumps, obstacles, and people, which made reading feel awkward. Of course concentration and speed of reading varies by each individual, and some readers are more disposed to reading-walking than others. I loved walking along the Truckee River, but as a reader I prefer to read this poem, or probably any long text on a screen or a page, to reading it on the pavement.

Second, let’s consider the poem’s environment in more detail, and how it affects reading. I only walked along the mile where the poem appears, from the Riverwalk District by the downtown casinos, to the leafy area to the west, where middle class residential neighborhoods meet river-adjacent city parks. I arrived in late October in the middle of the week, as the weather began to turn toward winter, when the warm weather revelers had flown. Downtown, people were scurrying to get somewhere else, to work, or home, to a casino or a hotel; others walked at a slower pace, carrying all their worldly goods in packs or shopping carts, while still others sat on benches in riverfront plaza areas, warming up, drying out, or hoping for a lucky break. Everybody seemed to be in “survival mode,” and few seemed likely to focus on the poetry on curbsides, distant from the immediate physical presence of the river.

When I walked to the leafy zone to the west, the river had a more powerful presence, and walkers were more rooted and secure. They were usually exercising, walking their pets, or conversing with friends, and taking in the beauty of the sun and sky, the river and nearby mountain ranges. This area seemed like a more favorable environment to stop and read in.

But even in this more contemplative setting, a reading of a long section, or even just a stanza on the pavement required some effort. Being outside can be pleasant, but as we walk and try to read, our multi-tasking evolutionary minds also want to pay attention to nearby noises and scenes: cars, people, animals, and bicycles approaching from behind or in front of us. Then there are more benign factors, like the sound of the Truckee River, the wind in the trees, and the sight of the sun and clouds in the sky, that compete with a reader’s concentration on the text. Autumn leaves accumulated and covered up sections of the poem. More worrisome a month past installation, sections of the script had peeled off of the pavement.

Most of the long poem is west of downtown, much of it only a few feet from the Truckee River. The poem, and some environmental education plaques, offer readers cues that the river and the poem parallel each other, which could give great pleasure to a reader. But how many readers will balance the environmental “distractions” with reading efforts, going beyond a well-turned phrase to realize that something more profound is afoot? Walking-reading about watersheds by a river promises a kind of synaesthesia, but reading a long text outside involves distractions. On the “spur” streets, where the poem radiates away from the river on sidewalks and especially on curbsides in busy areas with people coming and going, reading may be even more distracted.

Third, textual issues affect reading as well, starting with what kind of text the readers think is being conveyed. Unless viral publicity sends a wave of poetry lovers to Reno to read “Confluences,” many walkers will ignore it, or view it as an obscure irritant, like graffiti. Others will read a phrase, but unless “hooked,” will disregard it without a second thought. The more open-minded readers that allow themselves to be hooked, distracted from enjoying the scenery, may feel beguiled, but will wonder what these words are for in this place. If they persist in reading, there are several medallions periodically affixed to the pavement, briefly explaining that this is a poem about watersheds.

Some artists try to deal with short attention spans by slipping deep messages in, using short, facile slogans and appeals to ironic effect. Those who specialize in creating “word art” for public spaces, like Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger, have used witty placement, and clipped phrases that mimic ads, often with meaning thrown askew, to reach an audience in seconds. Todd Gilens tried this in 2011 using images, coating some San Francisco buses with giant wrap-around photos of animals (one per bus), each belonging to a local endangered species evoking notions of vulnerability or freedom. These enormous images moving through traffic worked as ads work: the striking image, the momentary response, and the momentary question: “why endangered?” His pavement poem has a different strategy: rather than making a flash impression, it engenders ponderous thought. The poet’s choice to install it along the Truckee River, where nature meanders through the urban grid, follows from his aim to make readers meander.

A long poem always presents challenges. In print, it encourages a highly recursive kind of reading; readers circle back in the text to savor a sound, or clarify a new or old meaning. But when the text is on the pavement in a long single line, re-reading means walking back to that special spot again on the pavement, and once again reading ahead to where you left off. But your typical walker-reader won’t go back.

Momentarily, I considered the pavement poem’s long single line, to be like a spoken word poem, where the words are uttered in a stream, and cannot be reviewed as in a silent reading. But the poem does not use the song-like refrains, melody, and chanting that allow bards to stride forward into new realms without losing their listeners. Melody of course is not available in written language. Repetition is, but in this poem it is only used lightly, if at all.

What about printed poetic devices that help readers to focus? “Confluences” uses sentence structure, punctuation, and capitalization to advantage. But not line breaks: in my walking-reading, I did not perceive the line breaks of the poem’s screen version. Todd Gilens says line breaks can be felt in the poem’s phrase structures, which correlate to walking-reading. The phrases in this long ribbon of words were supposed to function like individual box cars on a long freight train, but they didn’t work that way for me. Walking along, I could see the freight train of words, but as a reader I could not sense a phrase, its powerful weight in one “boxcar” linked to the next one, in the same way that I could in the screen version I had read before. Stanzas and sections, so important to meaning in printed or digital poetry, are often not available in this ribbon-on-the-pavement version at all.

Todd Gilens has worked for the better part of a decade following researchers, writing proposals to agencies and foundations, inventing an original font based on one man’s handwriting, calculating the poem’s spatial dimensions to fit its words onto sidewalks and curbsides, working with digital printers to cut the lettering stencil-style, so it could be peeled off the backing, and affixed to a mile of pavement by Gilens and a team of four assistants. Now his words are coating the hard surfaces of the pavement. But people and animals are trodding on them, sometimes scraping them off. Leaves, pebbles, mud and dew are settling on them and being blown away. Rain and snow will pelt them, ice will freeze them, and soon, in only about a year, they will be peeled away and gone.

I imagine that Todd Gilens will eventually publish this poem, but its presence on Reno’s streets could fade all too quickly if readers experience only an isolated phrase, without noticing its blend of watershed detail and global body concept. What meaning will remain for most readers? Will a different kind of reading be improvised? Will readers will encounter these bright yellow words in flowing script and feel as they do when they see a dandelion growing between the cracks on the freeway? I am not sure.

With the help of Todd Gilens, I wrote this in 2023, with the intention of publishing it in a magazine or on-line journal focused on poetry, or the environment, or both. That was not to be, so here it is on my little blog, in all its essay-istic glory. If I could inspire one person to visit this site poem, I would feel accomplished, so if you do, drop me a line!